Taking Steps to Prevent Suicide

Though difficult to talk about, suicide is a growing public health problem in the United States. It is also one...

October 5, 2022

May 31, 2017

Mercy Home for Boys & Girls recently presented an online seminar, “Engaging Students Who Have Been Impacted by Trauma and Adversity.” Liz Tomka, Director of Academy Resources, and Andrea Simari, School Resource Coordinator, hosted the webinar for Chicago Public School teachers and others who work with students impacted by trauma.

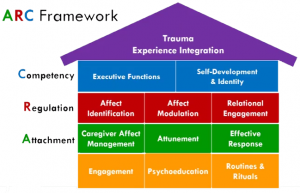

The webinar educated viewers about the impact of trauma on the brain and learning, along with strategies on how to engage students in the classroom and school environment. Such initiatives were all rooted in the Trauma Center at the Justice Resource Institute’s Attachment, Regulation, and Competency (ARC) framework, the basis of Mercy Home’s model of care. The presentation also outlined effective responses to adverse student behavior and provided an opportunity for additional resources to become a trauma-informed school.

Trauma can be divided into four categories:

Consequentially, those who work directly with individuals who’ve endured trauma are vulnerable to experiencing what’s known as vicarious trauma. This describes the emotional residue of exposure that counselors and teachers have from working with people who share their traumatic stories, thus making them witnesses to the pain, fear, and terror that trauma survivors endured.

Prior to Mercy Home, Tomka worked at a high school in Chicago with high-needs students.

“My students were experiencing community violence, as well as they each had their own individual histories of trauma – often abuse or neglect,” she said. “As a result I was also taking on that trauma. It took me a while to realize that, but we can all be impacted by our students’ trauma. Whether you’re a counselor, a teacher, school staff, school clerk, you can be impacted by the trauma your students are experiencing.”

Tomka stressed the importance of teachers and workers practicing self-care, but also viewing themselves as caregivers in the lives of students.

“To be effective caregivers, we need to know how this vicarious trauma is impacting us,” she said.

Doing so means understanding some core principles: Trauma shifts the course of healthy development. Trauma does not occur in a vacuum, nor should service be provided in one. Good intervention goes beyond individual therapy.

First and foremost, caregivers must remember that trauma-effected youth are simply not a composite of their deficits, but are whole beings, with strengths, vulnerabilities, challenges, and resources.

“That’s where we come in as some of those resources,” Tomka said. “The framework seeks to recognize factors that derail normative development, and work with youth, families, and systems to rebuild healthy developmental pathways. Systems is really where we come in, and the school system is really a critical part of that.”

Caregivers can then begin implementing the three pillars of the ARC Framework.

Trauma-effected youth “need relationships with adults to become resilient, and this is one of the things they struggle with,” Simari added. “The takeaway for caregivers and teachers is that you can be that person that can make the child resilient.”

Watch the webinar to learn more about engaging students who have been impacted by trauma and adversity.

Though difficult to talk about, suicide is a growing public health problem in the United States. It is also one...

October 5, 2022

Camp is more than just a vacation - it's a chance for healing, too. Nature provides many therapeutic benefits that...

June 9, 2021

By understanding child abuse and neglect, you can spread awareness about the issue and prevent child abuse from happening in...

April 8, 2021

Comments