Young Man Finally Finds Home

Jace’s path to Mercy Home began with the worst night of his life. It had been building for a long...

October 8, 2025

July 23, 2020

Community Care Scholar Triumphs, Thanks to Education, Discipline, and Donor Support

Mercy Home prides itself on its personal, hands-on approach to helping young people heal from past trauma. But sometimes the best outcomes are achieved by holding on loosely without ever letting go.

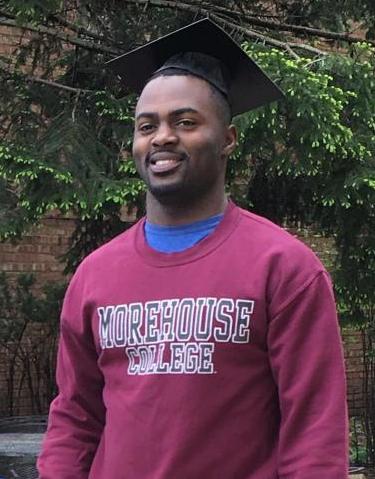

For example, take Wayne—now a 28-year-old loving husband and proud father of a two-year-old girl. He’s one of Mercy Home’s Community Care scholars and a recent graduate of Morehouse College. By giving Wayne the freedom to learn from his mistakes and carve his own path, Mercy Home helped him find success on his own terms.

Wayne has a mind like a free-roaming mustang. When he speaks, raw energy and passionate ideas gallop forth with power and instinct. Informed by his Afrocentric single mother who attended Princeton for a time, young Wayne—ever the freethinker in school—had a reputation for challenging the powers that be and correcting his teachers.

When Wayne was in middle school, his obstinacy got him kicked out of class and in trouble with the law, which led him to Mercy Home. His obstinacy also led to his decision to leave Mercy Home on his own accord when he was 14 years old. But Daniel Nelson, director of our Community Care program—which offers ongoing support, encouragement, and resources to former Mercy Home residents—always kept Wayne within sight.

“My mom begged me to stay. She didn’t want me to come back to the neighborhood and get in trouble,” Wayne said. “Honestly, I shouldn’t have left Mercy Home. It was an impulsive decision and it led me to make decisions that still affect me today. But even after I left, Daniel would call and stop by my house as much as he could. He was always around in some shape or form. And that’s what eventually led to me coming back as a scholar.”

Over the course of Wayne’s evolution— from gang life in the streets to graduating from one of the most prestigious HBCU’s (historically black colleges and universities) in the country—his mentors all came to the same conclusion. For Wayne to reach his full potential, it wasn’t so much that he needed to rein in his tenacity; it had more to do with harnessing his perseverance and channeling it toward positive results.

The discipline required for such an evolution meshed well with Wayne’s fascination with history, martial arts, and the strategy of war, not to mention his family’s tradition of military service. But before he found solid ground, he was adrift.

“I went into this big, deep depression. At one point, I was borderline suicidal because I felt like I had lost everything—a lot of my friends were dead or dying in the streets, and my brothers were locked up,” he said. “That was the point in my life where I hit rock bottom.”

Roaming the streets one day, he walked past a gym and saw people wrestling, rolling around, and doing Brazilian jiu-jitsu.

“I walked in and knew that’s what I needed to do, because extracurricular activities always kept me out of trouble,” he said. “I’m more passionate about martial arts than anything, because honestly, it’s the thing that saved my life.”

Unable to afford membership, he worked out a deal with the gym’s owners: they would allow him to train if he wiped down the mats and cleaned the toilets. As he trained furiously, he also started an internship as a community organizer. His roommate, an alumnus of Howard University, introduced Wayne to an intellectual circle of lawyers, teachers, and activists. When Wayne admitted he felt out of his league with this group, his roommate gave him a pep talk.

“He told me, ‘Wayne, you have discipline like I’ve never seen. You have so much potential and I don’t feel like you’re capitalizing on it. You need to go back to school. I see the way you train for martial arts tournaments. There’s no reason why you can’t sit down, take notes, and get good grades.’”

“That’s when the light bulb switched on,” Wayne said.

The summer of 2014, Wayne enrolled at Truman College in Chicago, where he eventually became president of the African student union. After earning his associate’s degree, an administrator encouraged Wayne to consider Morehouse College, not only so he could continue his education, but also so he could escape the city’s gang violence.

Gearing up for his move to Atlanta, Wayne loved that Morehouse was founded in the wake of the Civil War—that its first students were emancipated slaves and black Union soldiers who were getting educated to become teachers, doctors, and lawyers.

“I felt more of a cultural and ethnic connection to Morehouse,” Wayne said. “I come from an environment where the majority of my enemies—the people who made life hard for me—were black. I started to internalize these negative stereotypes—how I viewed myself and my own people. But when I went to Morehouse, surrounded by black excellence, it just totally erased those feelings.”

Inspired by Morehouse alumni, like civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr. and filmmaker Spike Lee, Wayne relished the intellectual dialogues he suddenly found himself taking part in on campus.

“I was blown away,” he said. “I’d never had these conversations with people my own age.”

Anchoring himself in this vibrant community, Wayne worked two jobs while attending school and also served as the vice president of the Morehouse History Club. When he and his wife became parents, juggling childcare, work, and school responsibilities became a challenge. Some days, Wayne had no other option but to bring his daughter to class. Morehouse’s community not only supported this move, they encouraged it.

“That has a lot to do with African-American culture,” Wayne said. “We tend to go on that ‘it takes a village’ mindset to raise a child.”

During one algebra class, Wayne’s professor offered to hold his daughter so Wayne could take better notes. A fellow student posted a photo on social media of the professor teaching with Wayne’s daughter strapped to his chest. The photo went viral as thousands of people shared the post in praise. But Wayne says this happened all the time at Morehouse. In the library, study hall, and cafeteria—all across campus—people always lent a hand.

“I had babysitters everywhere,” Wayne said. “Everyone loved my daughter.”

Now with a degree in kinesiology, Wayne is excited to begin his next chapter and pass along what he’s learned to the next generation.

“A goal of mine is to establish a community program where I’m teaching martial arts skills, as well as life skills, to inner-city, at-risk youth,” he said. “In another year or two, I also plan on taking my LSAT and going to law school.”

Wayne’s clear vision for his future is a reflection of the love and support of Mercy Home’s generous donors. Thanks to their commitment, he has a firm grip on the reins and is steering his life in the right direction.

Jace’s path to Mercy Home began with the worst night of his life. It had been building for a long...

October 8, 2025

On the street where Eric grew up, the flashing blue lights of police cars were a common sight. Neighborhood violence...

September 2, 2025

On the street where Eric grew up, the flashing blue lights of police cars were a common sight. Neighborhood violence...

August 28, 2025

Comments